Zur deutschen Version

Olga Neuwirth

Camouflage, Ironic Distance and Acoustic Rage

My personal history with DIE STADT OHEN JUDEN (THE CITY WITHOUT JEWS) goes back to the 1980s when I was intensely searching for my identity. While doing so I went on a private guided tour through the Museum of Natural History in Vienna, I noticed some neglected looking objects in the museum’s collections. It turned out I had accidently stumbled upon the suppressed history of a collection of the human remains of murdered Jewish citizens. They had served as anthropological research objects. Shocked I told Elfriede Jelinek of my discovery. She incorporated my description into a chapter of her book Die Kinder der Toten (The Children of the Dead —1995), and that got the ball rolling. It came to the first public debate on the subject, as well as restitution proceedings and the burial of these human remains. It was also during my “identity search” that I read Hugo Bettauer’s incredibly clairvoyant and visionary book Die Stadt ohne Juden (The City without Jews) written in 1922. And shortly afterwards, I saw the unrestored version of the silent film. So I knew the Die Stadt ohne Juden well when in 2016 I was asked by the Wiener Konzerthaus to compose music for the world premiere of the newly restored version of the film.

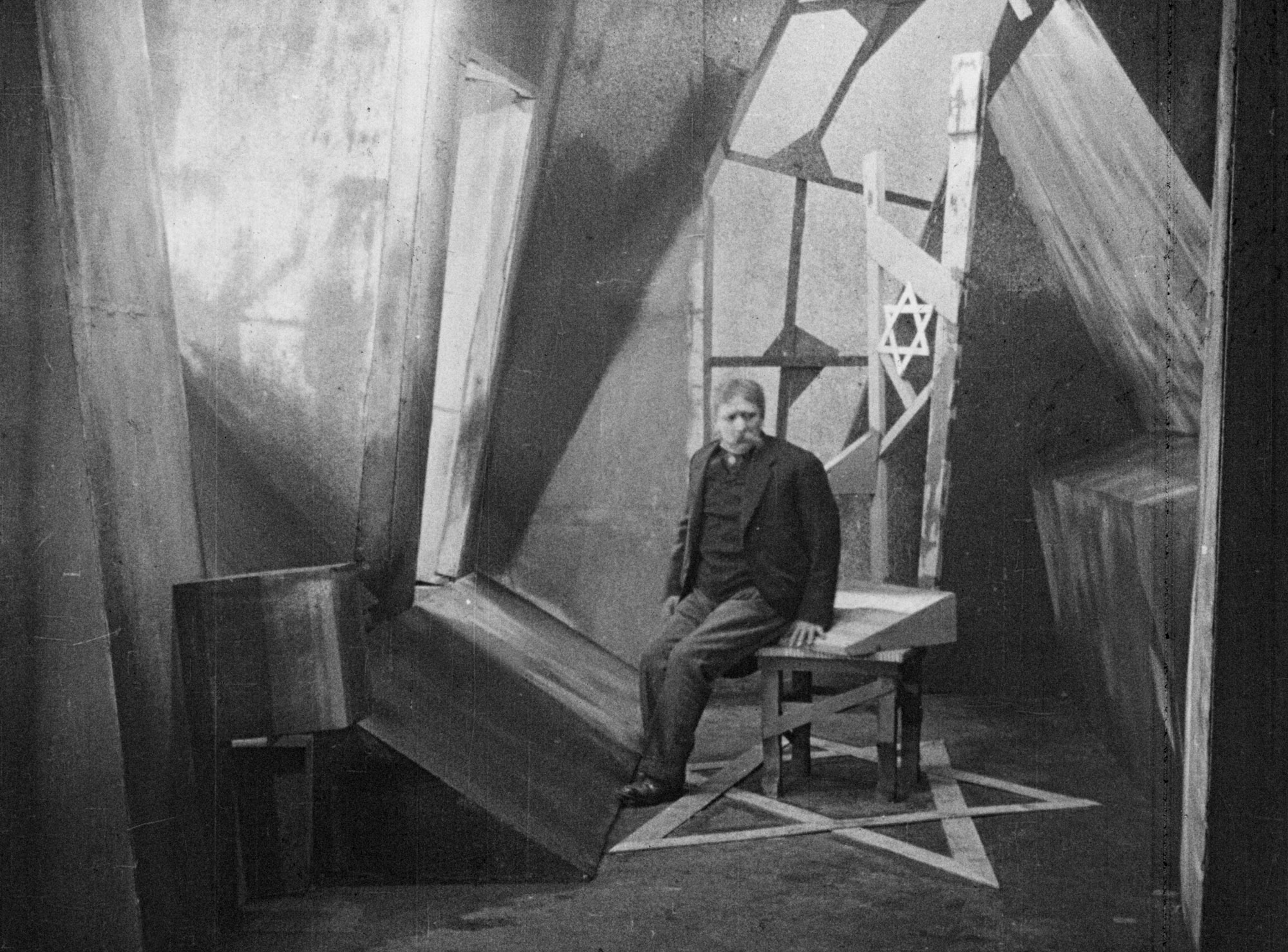

Today, because politicians are again making hollow formal excuses for racism and everyday hate campaigns, we must put an end to the trivialization of linguistic terms passed down to us. Hence it was particularly important to me to draw a connection with my music from the past (1922/1924) into the present. Also hatred towards Jews is increasingly being expressed todays, ever more bluntly—even in Western democracies. Hatred has not disappeared, but was, so to speak, merely absorbed. Indeed, the time has come to stop feigning ignorance and playing down the slogans that are inundating us. The Film Archive Austria has meticulously restored the film, which is rich in gestures, facial expressions and extremely theatrical performances, some of which veer off into grotesque exaggerations. Made in 1924 and based on Bettauer’s novel, the film seems like an apocalyptic vision of what would later become reality. Journalist and author Hugo Bettauer, was murdered in his office by a young Nazi only a few months after the film premiered. The murderer was never convicted as he had the protection of anti-Semitic lawyers and influential politicians.

Composing music for this silent film is thus a huge responsibility. It goes without saying that with a medium as fleeting as music, I cannot deliver any sort of objective truth on the film. After analyzing the film material, I could therefore only try to give my own personal musical take on it: a mixture of complexity and productive uncertainty, by applying camouflage techniques, combined with an ironic distance and acoustic rage—at the cruelty of humans out of pure selfishness, greed and envy. By using citations, I wanted, among other things, to refer to the jovial quality that was also typical of National Socialistic language and that is being used in the exact same way today. The desire to understand mechanisms such as power, populism and anti-Semitism has always played a significant role in my life. Political engagement was and is my attempt to increase my awareness of the shameless and uninhibited outpouring of resentment, which can now be observed everywhere. The book, which Bettauer subtitled Ein Roman von übermorgen (A Novel on the Day After Tomorrow), was also conceived as a scathing satirical analysis of the circumstances of the times. Before the Shoah. Unlike the restored film, the book ends with Vienna’s mayor cynically and hypocritically cooing: “My dear Jew …” If an Austrian greets you with “My dear…”, then you immediately know: Watch out! As drastically depicted in the book, the crowd which had just been euphorically shrieking that all Jews should be expelled from the city, starts cheering when the Jews are asked to return. At the end of the book, Bettauer describes this with bitter irony: “to the sound of fanfare and blaring trumpets, the Mayor of Vienna, Herr Karl Maria Laberl, went out on the balcony and stretched out his arms in a gesture of benediction….” Every time I hear the name Karl Maria Laberl, I start laughing because for me it is a clear reference to the founder and leader of Austria’s Christian Social Party (CS), Dr. Karl Lueger , who by 1887 had professed his anti-Semitism..

The German National and Christian Social factions (which are also mentioned in the film) joined forces in 1888 to form an alliance for Vienna’s municipal elections: later they became known as the United Christians (Vereinigte Christen). At the time many young clergymen believed that social problems could be solved by resolving what became known as the “Judenfrage” (“Jewish question”). Lueger’s anti-Semitic rhetoric gained widespread popularity. Just as the word “Laberl” has several meanings in Viennese (e.g., “little meat patty”, “small loaf”), the name of Austria’s chancellor in the film, “Dr. Schwerdtfeger”, has a subtext (e.g., it sounds like “someone who sweeps everything aside with his sword”, or even “a sword-waving go-getter”). Initially Chancellor Dr. Schwerdtfeger responds with reserve to the idea of expelling the Jews, but then for tactical and egotistical reasons moves to make himself the ideological leader of this movement. He delivers emotional speeches before parliament on why it is impossible to co-exist with the city’s Jewish residents. In doing so, he seizes upon a number of stereotypes that strongly coincide with anti-Semitic rhetoric in general, and the way individuals voiced their opinions at the time. In 1899 in Vienna, Karl Kraus called anti-Semitism „the disgrace of the century”. iHe did not believe in the press’s methods of veiling matters by making them appear ridiculous or in surrounding them in a deathly silence in order to play them down. Like Karl Kraus, Bettauer was an analytical journalist who was critical of the times. Similar to today, people’s lives were dominated by three basic experiences: a sense of loss, the threat of losing their socioeconomic status, as well a mood oscillating between a culture of revolution, vendettas and agitation—such as often found today in counter movements or public opposition via social networks. And inflation and unemployment exacerbated the tense situation. Populism was and is used to fuel social imbalances and divide the rich and the poor, city and country, locals and foreigners /in- and outsiders.

Current parallels to these hate campaigns and contempt are terrifying. The book, which I read again, as well as the film had a shocking effect on. Not only because of the anti-Semitism that was openly expressed in the streets again during the “Waldheim Affair” in 1986, putting an end to the lie, namely, that Austria was Hitler’s first victim—but also because of the same mechanisms that are repeatedly employed to win over the perfidy of the “Austrian soul” for diverse purposes. But also because I am troubled by the fact that populism, racism, xenophobia and anti-Semitism are still being practiced and instrumentalised in election campaigns worldwide and so furthering the division of society. No longer do you have to let such “nonsense” as the legal system or the protection of minorities get in your way/hold you back. In this sense the film—and more particularly Hugo Bettauer’s book— is extremely topical.

Back to the music. There’s no simple answer to the complicated relationship between image music for a film that due to its subject matter was a prophetic vision. Of course, I don’t want to fall into/indulge in pure representation or “Mickey Mousing”, as Hanns Eisler called it, but sometimes I do anyway, that is, if I think it is necessary—and again and again with bitter irony. For despite how paralyzed I felt (also because not much seems to have changed since the publication of the book in 1922), and to avoid clichés even if I often allude to them, I have tried to retain a liveliness by making the music both touching and tough, heart-warming and open, amusing and angry, involved and aloof, humous and sad. It is not only about the anti-Semitism deeply rooted in the Austrian soul, but also about identity and Otherness, home and flight. To just mention a few of the “techniques” I applied: I took and transformed several fragments by Austrian yodelers. They are on the sample that runs throughout the film, although they also appear in some instrumental parts. I’ve also used some very short excerpts of Hans Moser singing Viennese “Heurige Lieder” (wine tavern songs). Hans Moser, who plays the anti-Semitic “Rat Bernard” in the film, was already quite famous, thanks to his appearances in Vienna’s cabarets and revues following World War I. He later became the icon of the typical wine-loving, melancholy Austrian who drinks to forget. In addition. the use of existing musical material can also be found in a fragmented quote from a song that has been used in Austria at rightwing populist election events in recent years.ii It frightens me with what devotion many people latch on to this kind of nationalist slogans and manipulative music. Yes, sadly, time and again, Austria has been a trailblazer for right-wing movements…

Translation: Catherine Kerkhoff-Saxon