Zur deutschen Version

Elfriede Jelinek

City without everything

What the powers to be say or do, is correct from their vantage point, is unconditionally true, because that vantage point from where someone does something or just observes is also in the territory of power. People with no power point their finger and say – no they whisper: whatever the powers to be say, whatever their formulations, their outward forms, they are only conditionally true, that means in truth, untrue. That’s where the face off takes place. If people without power had something to say, then two positions of power would stand face to face, each in possession of the unconditional truth, and no one would be lying. Yes, but each side in a house of representatives, representing and deciding what’s present, needs a two-thirds majority for the truth. That’s not easy. There are easier ways to get to the truth. But if everything is true, then everyone is lying. For the powers to be, something that can be true can also be false because if something false is the basis of power then what’s false would be true, and what is false would not need to appraise itself and pass judgement. That job goes to the represented and unrepresented people who most certainly don’t want to go. They want to come and get their hands and (need be their fists) on seats that become free. There’s plenty of beer and wine, and they serve decision-making; both are served up constantly, serving to distract people from themselves.

How can humor about Jews work knowing about the total destruction of European Jewry? Humor originates – exactly – it originates in not knowing…not knowing…yet. We can do nothing about it. Oh, if we had only known! From that discrepancy between knowing and maybe knowing … something could surface there. We can’t really see what yet. This film knows more than it knows because it cannot know what it knows. It’s riding on parallel tracks with itself. We know more. I’m not saying: today we know much more. Because we could always have known. If a film knew in the middle of the 1920’s, it was more than it could have known because it already knew it unbeknownst. And after that, people collectively lost that knowledge. And what we know in the meantime (and, yes, have always – even if it wasn’t just whiling its time with us but sometimes off on some summer holiday for a little relaxation) is of no use to us today when we literally ride right over it. On the one track there’s the Flying-Dutchman-Express, picking up people, spitting them out, taking others on board, a train that doesn’t know where it’s going, racing by on track, under the viaduct, but there’s no end to it, meaning it could just as well just be standing there; each car you see might be standing there and at the same time have just passed by. The next one would be the same. Just the faces behind the windows might change and the passing by would be what takes place nonstop at the same time. Just like when we look in a mirror and don’t know what we are (I didn’t say who we are). Even the tracks look pretty harmless, one for the transport, one for the return trip. Later they saved themselves the need for the return trip totally. For now, it is still possible. The way the tracks fade in the distance looks almost elegant like in that famous poem by Heine about the sunset. It’s an old trick. It goes down ahead and returns from behind. As easy as that. This way and that way, on the whole, not too difficult.

Sometimes amicable, sometimes amiable and in some parts heartbreaking too (one of the Jews being deported bends down and picks up some earth from home and puts it into his handkerchief) and then the film gets funny again, especially because of Hans Moser in his second ever film role. And look at that, he’s the missing vote for a two-thirds majority. The zero everything depends on, on one person, and it turns out to be him of all people! Him! A dope! A comedian! We’ve been adding up the numbers like crazy, and it’s true! He’s the hair of the dog that’ll break the camel’s back. And just at that moment, he trying to open the front gate to the house with his cigar! Holy moly…holy Moses! That’s the kind of humor which likewise is supposed to undermine itself – by showing the discrepancy wide open: that – and this is a fact – humor can never get into power. Completely unimaginable because there’s no one against it, no one to get chafed. It keeps trying anyway like some bad joke about boxer shorts and bloomers or some rock and some hard place where they all get stuck. But then we’re out of there again. Just look, the bumpkin comes to town, wearing some Alpine get-up and tourist duds! A guest at home, which as everyone knows is the best place to relax…just being yourself. Countless comedies feed on that (it’s even funnier when the person who has the say but doesn’t know what to say except for stupid things comes in on his high horse. That’s when power gets dangerous – in this case for the belly, when we burst out laughing haha). But we’ve got other ways, dear guests! This humor about the victory of some massive power has other ways at its disposal, when it finally gets on its high horse and doesn’t know its own mass anymore, except maybe for mass media, and that’s how it presents itself, still from its supposedly best side. It’s always that way when the powers that be are not aware of their intrinsic humor and consider themselves a force and not a farce of nature. That’s when the heavy and serious drifting towards dissolution begins. We have forgotten our own mystery, and then at the same time you see…we’ve got other ways, we want another way. Jews can be useful creatures, beautiful like rose chafers, but maybe it’s better if they be that way somewhere else where you don’t have to see them, see how they damage things. We’ll show em! Either us or the Jews! Don’t have to think about that too long. Even laughter is almost always ambivalent. Kafka writes in a letter to his sister Elli (he describes it as a “romantic adventure”) how a crowd of girls from a school in the Botanical Gardens goes by in the sunlight, and an especially pretty, tall, blond girl, she looks so young – that’s how Kafka describes her – smiles at him flirtatiously and says something to him. Kafka smiles back trying very hard to be friendly, the way you do in situations like that, but only later does realize what the girl actually said: “Jew”. That’s what she said to him.

The caricatures of rich, debauched finance Jews, presented as if they manipulate the currency system just sort of on the side and catapult their host population into bankruptcy and then… where to?, back to their hosts of course! Yes, that’s something they can always do with their money and their international connections and are glad to. Otherwise they would never have gotten so rich. But we always knew that. Money is what they produce and it’s what they eat. That’s the way we’re supposed to see them here. The humorous distortions are the result of the discrepancy to themselves. They are viewed in a way they would never view themselves, which still doesn’t mean a discrepancy between life and annihilation, because they couldn’t have imagined there was something they couldn’t know. In that respect they knew everything. For the powers to be this discrepancy is not important. For those without power it is a form of expression; they need to know what others don’t need to know. And the powers to be will soon be another’s to have. Cripples are not supposed to call themselves that. We aren’t supposed to either. You see an attempt that demands the utility of people and which can be revoked any time, sometimes even when we know better – that’s always something only the master race can judge: whether everyone gets to keep their position, whether they work at a lady’s fashion shop or at the bank – , a utility that loses its validity the moment the majority decides against it, even if that means deciding against usefulness itself…because the Jews wanted to be useful, make themselves useful. But they were already condemned even if the film can only hint at that because it tries to confront power with elegance and beauty and amicably and tries to disagree because we don’t need these things anymore. We’ve got other things. (Power doesn’t even know what those things are, because it doesn’t need them; what it needs is human flesh, that’s all it eats anyway. It doesn’t make a difference if that flesh is in a silk dress, a fur coat or in lederhosen wearing a hat with a feather in it and sitting at a table in some tavern or standing around a bar drinking wine. At the end, they all get their turn. Even the clothing in this film professes more truth than people could ever express in words. The father of Kafka’s Milena sent a loden jacket to her in the concentration camp to keep her warm. If clothing is no longer innocent who or what can be?). Either we ruin ourselves, or the Jews have to disappear. Let’s save ourselves and our children from them. Our grandchildren will thank us! Maybe we’ll have to – umm temporarily – make a sacrifice in certain areas, but in our great beneficence (and so our neighbors won’t rise up against us) we’ll find a kind and gentle way. As usual, where kindness and gentleness are involved, the next step is making regulations and writing down exact details: what the refugees may take along, how much and what not. And naturally, when it comes to determining who gets expelled, we decide. Meaning: All of em! Righteous but fair, that’s our right. In Bettauer’s novel it sounds like he’d read the Nuremberg Laws on race and was at the Wannsee Conference. The truth of power is always false, but the victims are real. They can offer their services, but they get cut off like hands reaching out in vain for something. And…we’ll never forgive them for that.

In “Jokes and Their Relation to the Unconscious” Freud tells an old joke about a celebrity who people say has a great future behind him. There’s nothing else you need to know about that person. The joke is a put off and a put down. Maybe in this film you can also speak about a joke and how it relates to what everyone knows. Everyone is aware (and they say so too): the Jew has got to go. We have no future with him. Soon we’ll have the Jew behind us and finally the future before us (which can only be because we had such a fantastic past with the Jews but they’ve missed the train now and have to be trained for something else, because the future finally gets its turn – we’ve waited long enough). That turns every joke into its opposite on the spot because the joke’s gone topsy-turvy. On the spot conversion is the thing, but no one dares say it though everyone knows it before it’s true that the future is truly out. But who wants to announce it? The project called Return is characteristically initiated by an artist. No one respects artists anyway. One attempt more or less won’t make a difference anyhow. Artists are used to that. One of them has an idea. Once is okay but once is already once too much (if we’d only caught him). “A Jew speaks in the language of the country he has lived in for generations but he always speaks it as a foreigner.”. That’s what Richard Wagner wrote in “Judaism in Music”. In the film, this applies to a painter. And this artist winds up saving everyone because one Jew is all Jews, or they’re all alike anyway! But first conformity rolled into the city, which the powers to be needed to keep tabs on everything, then some compulsory equality that had never existed rolled everyone and everything over. And then the wheels of the trains began rolling – and not for victory’s sake. Anyone who’s different gets booted out of the popular order of things any time, even those who used to participate or at least feel like they were partners. Survival in this city where people dance waltzes (but not much longer), where people wear silk, chiffon, makeup (but not much longer), this city speaks in the voice of the people which always imitates God’s voice, without ever having heard it because God has still not shown them his Aryan identity card and better keep his mouth shut. We’ll drive em to drink, the painter is thinking. The only solution here leads over a bridge of alcohol and grub, a bridge that almost collapses under the weight of it all. We’ll just take that suddenly so racially pure people using one of their noblest, guaranteed racially pure representatives and smother and drown him in the drink, but this time for a change in lots and lots of beer, lavish food and local music. Um tee da, um tee da um pah pah!! Just listen to it: that’s how the powers to be speak. They speak in this single voice. It can still be funny, and the music! music! music! is played in a voice that is all-inclusive, which is what the voice of music is used to being. Even the music becomes innocent, because it always was! And we’ll bash em like bugs, the Jews, say the powers to be, we, the Aryan people who took away their work and never gave it back, we even cashed in their money for it, we a people in the clouds have made this great sacrifice by expelling a minority. We had no other choice. Typical. First, we suffer so awfully because of this minority. You can hardly stand it…and then we’ve got to suffer because we expelled them! Everything’s against us! Everyone is against us – even we are!! Yep, that’s what happens when you’re in a position of power. First you offer services, but then who needs them anymore? Meanwhile the Jews we expelled (not the refugees of course, but those poor Eastern Jews. Nobody wants them anyway. They don’t count, we don’t even count them anymore. No one counts them. Let’s just say they are countless even when there’s just a few of them. They look so weird which is why you can see them so clearly. I mean, just the way they’re dressed. They’re going to turn us into paupers, and then, we’re all going to be somewhere in the East like them), okay, meanwhile the Jews we expelled, are still able to laugh at what happens when all that beauty which supposedly makes life worth living disappears with them. They can imagine what’s going to happen. While they still can laugh… they have already stopped laughing and have to pack their Torah rolls for the transit and scratch up some earth from the ground as a souvenir of the home they never had. And then life itself is worth nothing anymore. Naturally not our lives, no, never! We should be living it up.

The surface reflects, you see nothing behind it. But who needs to because this surface is all you get and some nice Shinola to boot. And y’know why? Because everyone sees it, and this everyone: no one. What? What they saw wasn’t even the surface? So, what did they see? No, the surface was everything already. That’s about it. The surface was cleared away but when the depth of the Aryan German spirit beneath was finally supposed to appear, heavy and substantial, something else came up: just the reverse of the Emperor’s new clothes: under the no clothes there was no Emperor – not even a naked one! There was nothing under there. A nothing on wheels that left no traces behind. And that was the only trace. The clothes for sure, they were there. They keep forever. Anyway, you can always have them altered. There was nothing else there. There was nothing else needed. You can’t turn a cover into a cover-up, maybe into a covert belief that is just a bunch of feelings that’ll work for one side or the other. You name it. Feelings are elastic. You can put them into everything. Come on, let’s open em up again and let em out. Was there something? No. Just a gap behind it, not the yawning kind, just the gaping variety. There is (and was)…as we have been saying…nothing behind it. But that nothing rose up and gobbled down everything over it, covering it. And afterwards, later, they covered all of Europe, armies, all wearing the same thing. It was not silk. Of course, things are different today, or maybe we should say: today some…thing…is different because that thing is impossible? Or because you just see it differently, meaning that you’d see it differently today?

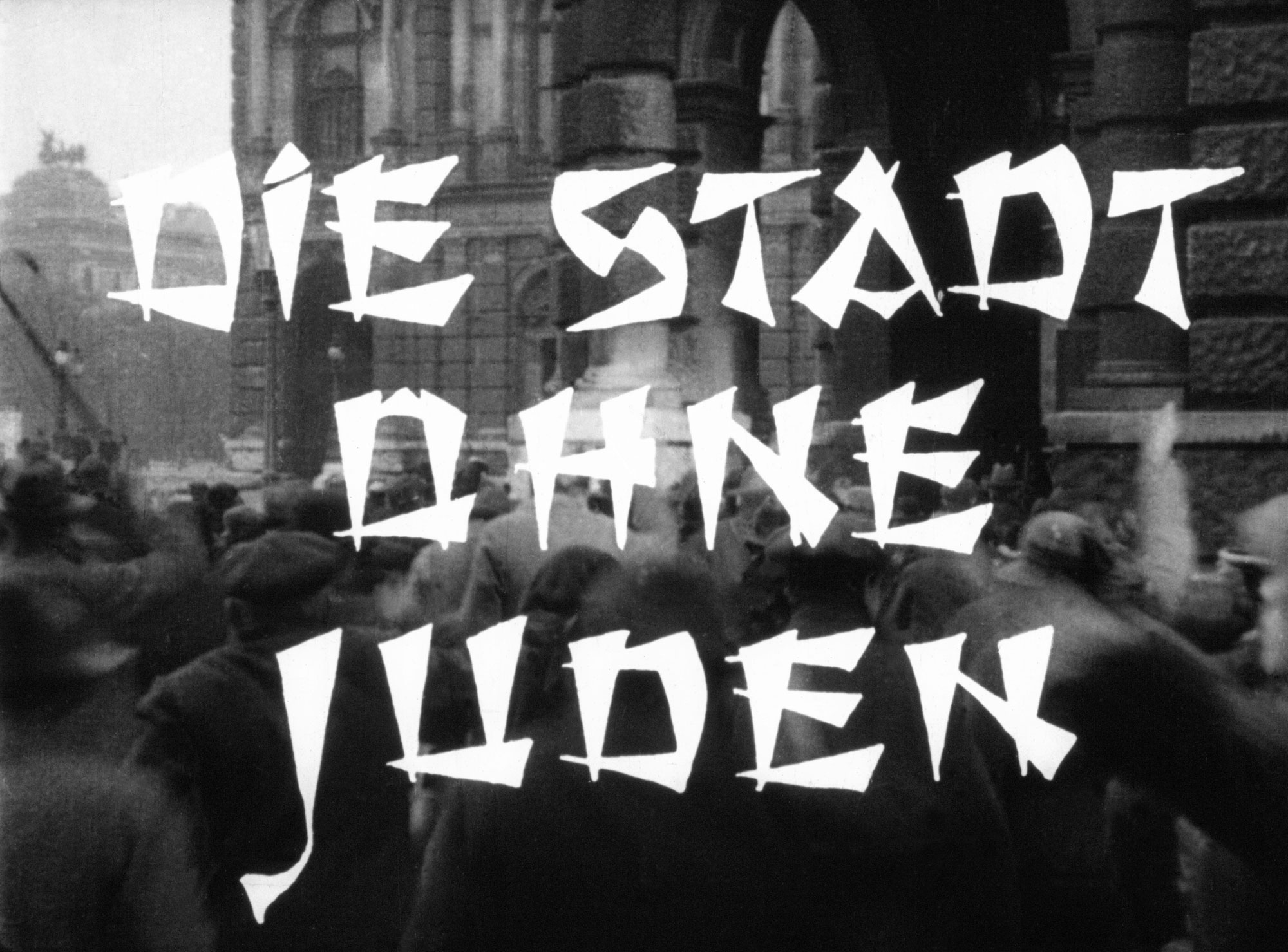

This lovability and livability (Hugo Bettauer, who just a few months later was murdered by an unemployed dental assistant named Otto Rothstock wrote a nasty little parable which was turned into a likable, witty film. But all that likableness is even more horrible because of the discrepancy to the horror that followed) are replaced here by some vague inkling about life unworthy of life. Just wait…soon. They are not worth it; they are worth nothing. Once the rulers figure out how things are when we’re left with no charm and no elegance, then they’ll certainly reconsider so we can buy silk underwear and evening gowns out of satin again. Yeah, right! But no one – not even Bettauer with his perspicacity could have imagined the extent of the annihilation that would be coming. He himself was just singled out for murder, no mass product. But then the people turned into machines, and the machinery rolled out and ran us over. Then there was nothing left, even if there was something we call “horrible” or “terrible” at memorial celebrations, usually just cheap talk, horror clothing, blouses of evil. It happened in this Somewhere, in this little Austria, this eternal Wish-I-Were-Big. They all fell for it. The fantastic clothes with cloth appliqué, pearls, rhinestones, hanging in shreds once the truth became the measure of power and there was room for nothing else. There wasn’t even anything like profit anymore. Who profits from nice clothes? Who profits from elegant women in fur or fine materials? Yeah, exactly. That’s a part of it, and then you’re apart from it: Not even the profit those delightful Viennese invoke in the film is a part of it, and there’s no purpose either when everything turns to Krupp steel and is tough as leather and as supple as a riding crop (that’s meant for the girls among us. Today we have jogging pants and tops produced in our own country).

Suffering always brings on more suffering. Only power counts – and it empowered itself to do what it wants, backed by the hoots of hundreds of thousands, crowded so tightly together you can’t see what they’ve got on. But who cares? What’s most important, you’re a part of it, and the truth is not true as something useful but as power unto itself as Heidegger the philosopher of the new movement says – even though he’s not referring to himself. You can always exclude yourself. Something like that can’t happen to yourself. It always happens to others, people we don’t need anyway and send away. Out of sight, out of mind. What should I mind there? We don’t know. We weren’t there. Power demands equalization, a natural process even when it requires some work. And now they’re all wearing uniforms, civil, obedient, comfortable loden or sensible cotton, ventilated, which people unfortunately can’t always be. It’s not a high price if people want to live with their own. But the irony the way that huge fustian underwear is just an arm’s width from the ladies – they could have used it to keep any man an arm’s length away even before he got there (anyway Catholic men always focus on inner values), that irony which requires some distance to yourself and to what’s been said – said and done – melts away slowly when there’s nothing to laugh about. If that ironic distance is lost, no, not lost but exposed and not under fancy shoes for ladies but under a dice cup, that’s when that coveted absolute uniformity power loves so much finally takes over. Power never laughs. What for? Maybe it lets you laugh at the film theater – but you can switch off the electricity there anytime. Let’s give it what it needs! Now it belongs only to us! We can do with it what we want. Power by nature demands uniformity and the production of a unity which, need be, just needs to be imposed because we’re not really that needy. It’s as easy as that…or not. Everyone pitches in. The departure of the Jews is done, the trains leave – and everyone is affected, even someone who’s the spitting image of some caricature from the Stürmer and explains laughing that he’s not a Jew! How lucky for him! This is still possible in the film. Later, even those who never felt Jewish or lived as Jews were sacrificed to the Totality without which there cannot be absolute power…the total power we want as long as it belongs to us. When the financial situation turns catastrophic and the workers no longer find work because the Jews took it from them, then they’ve really got to go. No, no no! Work’s going nowhere. But who are we going to get it from? We get it from the employer who usually isn’t there anymore. Who is in control of the press and public opinion? The Jew. Who’s piled up billions and billions? The Jew. Who’s got positions of power in the major banks and in almost all corporations? The Jew. Who, who who??? And what else is he doing? He splurges in nightclubs, fills the cafés and restaurants and drapes women in jewels? The Jew. He also writes plays. He paints pictures too. Count it up for the last time, honored guests. Just count slowly. The minority has got to go so the majority will have it better. That’s reason enough. Who’s counting how many millions it’ll turn out to be? It’ll be well invested. Won’t that be swell!

And Olga Neuwirth’s new music for the film – as opposed to the usual honky-tonk of silent film music – demands truth in so far as music is capable of expressing truth. The music wrenches open the discrepancy between the innocence of a film which consists of light and no light and what we already know for sure (though it hasn’t taken place yet). Between the rippling wave of the cheering backs of that tribal abra-cadaver that has just removed the Jews – hey we gotta celebrate! – and the slow, faint echoes of synagogue music almost dissipating in the diffused buzz, between the swelling nationalistic murmurs accompanying the phony joy of reunion and the goat song of the ever and always cherished folkloric um-pah-pah: suddenly the sharp blade of Chancellor Schwertfeger’s arrogated motives is exposed. For one moment, the trumpets tear the celebrating people (as long as there’s something to celebrate) apart. Then the guards go off to sleep. Anyone who still wakes up, he’ll gets to see! Anyone still cheering gets to see himself.

(Übersetzung: P.J. Blumenthal)